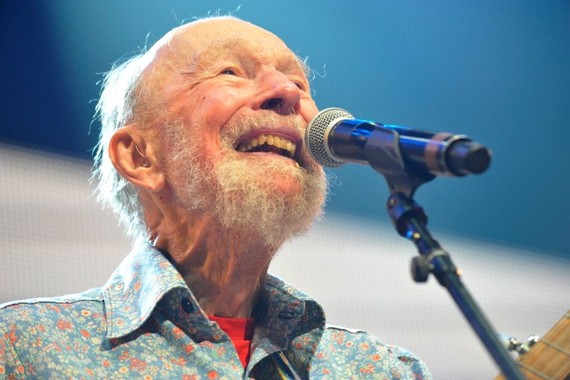

Life According to Pete Seeger: No Computer, No Records, Just Singing

The 91-year-old folk legend still believes in the power of song to transform society.

The 91-year-old folk legend still believes in the power of song to transform society.

Performing on the Late Show with David Letterman in 2008, Pete Seeger did the unthinkable: He waved his hand at the other performers and halted his band mid-song. For a moment, his backing musicians fumbled awkwardly at their instruments, watching the singer for cues.

"You know what, you can sing this chorus with us," Seeger told the studio audience. He began teaching the lyrics to his new tune, "Take It From Dr. King," an upbeat, syncopated number that memorializes the Civil Rights Movement and attests to the power of music to aid social change. After an impromptu run-through, the band struck up again, and the audience pitched in on the chorus: "Take it from Dr. King / You too can learn to sing / So drop the gun."

Seeger, who's 91 years old, has been enlisting audiences in musical and social endeavors since FDR was in office. He first gained national attention as a member of The Almanac Singers, a largely overlooked collective he co-founded with Woody Guthrie and Lee Hays in 1940. The band played at pro-labor events and union rallies throughout the country, leading songs like "Union Maid" and "Which Side Are You On?," as well as Communist-friendly ballads from The Little Red Songbook. Many of his Almanac-era recordings are noteworthy for having true choruses: on the refrains, Seeger's tenor is effaced by the uplifted voices of other singers. It's as though the recordings themselves are meant to inspire participation, urging the at-home listener to join in.

In 2010 the singer is still working to preserve singing's centrality to active American citizenship. "I still lead songs all the time," Seeger said during a series of telephone interviews this month. "I give words to the audience." On some of his more famous tunes, like "Turn, Turn, Turn," and "If I Had a Hammer," he said, "I barely sing the words at all. I just shout out the words before a verse, and the audience does the rest." Seeger sees musical participation as a key part of social participation, and worries about how our culture has outsourced the task of musicianship to a small handful of expert entertainers. "In 1910," he said, "John Phillip Sousa wrote, 'What will happen to the American voice, now that the phonograph has been invented?' And it's true—parents don't sing lullabies to their children anymore, they'll put them in front of the TV to fall asleep. Men used to sing together in bars all around the country—now there's a TV or loud music there instead."

After spending an hour conversing with Seeger, a 160-GB iPod begins to look less impressive: the man is a walking repository of decades worth of commercial and folk music from around the world. He sprinkles his language with snippets of songs in different languages, moving easily between singing and speech while he talks. Considering many Americans struggle to remember the important phone numbers they've digitally stored, Seeger, who doesn't use a computer, is a Luddite monument to the human capacity for mental recall. And most of the songs he knows have been transmitted to him person-to-person, without electronic technology: "I have never in my life liked to listen to records," he said. "I'll listen if I'm curious about what a song is, but I don't like to have background music in the house. I can't do anything else while I'm listening to music. I'll have to try and play along with it." Even alone in his own home, Seeger makes music participatory.

In July, Seeger released a new album, Tomorrow's Children, his first since 2008's Grammy-winning At 89. The record features an unusual co-star: a group of fourth-grade students who live near the singer's home in Beacon, NY. Tery Udell, a teacher at J.V. Forrestal Elementary, asked Seeger to visit her classroom serially and teach her students songs. Seeger so enjoyed the experience that he decided to make a record with the class, emphasizing their vocal contributions.

The singer was so dedicated to his work with the students that he passed up an opportunity to be a privileged guest throughout President Obama's inauguration. The weekend before the swearing-in ceremony, Seeger and Bruce Springsteen closed out the "We Are One" concert with a performance of Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land," singing in front of President-elect Obama and a crowd of 400,000 gathered before the Lincoln Memorial.

But while the other musicians stuck around for the remaining days of inaugural pomp and circumstance, Seeger felt his home responsibilities calling. He had a rehearsal with the students the next day, and began looking into train and plane arrangements. Springsteen was so moved by Seeger's hometown dedication that he "made some phone calls, and my grandson and I went home by private jet," Seeger recalled. It was a rare taste of luxury for a singer whose records rarely sell over 20,000 copies, and who heats his Beacon home with wood he chops himself. "That was quintessential Pete," said Jim Musselman, founder of socially conscious record label Appleseed Records, which releases Seeger's late-period work. "He'd rather be trying to do something in his community, or do something with kids, than something much more high-profile. He's lived his whole life that way."

Together, Seeger and Musselman have a history of turning down money and attention in order to stay true to their beliefs. In March 2009, Appleseed Records was approached by pre-spill BP, who wanted to license one of Seeger's songs, "It's a Long Haul" from At 89, for a commercial. "It was going to run in the US, Australia, South Africa, and all of Europe, and parts of Russia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands," Musselman said. The company offered Seeger $25,000 to use the song in the US and a much larger price, which Seeger said was "in the hundreds of thousands of dollars," for worldwide use. "I told Jim not to let them use it, and he agreed," said Seeger. "I'm not rich, but I make a good living from royalties from my songs. I didn't want to ruin ["It's A Long Haul"] for a lousy commercial, which is connected with war for all we know." It's a striking move in a musical climate when corporate patrons provide key financial windfalls for musical acts, even ones who are referred to as "indie." (Grizzly Bear, Maps & Atlases, and The Violent Femmes, for instance, can be heard respectively in recent commercials for Volkswagen, Nintendo, and Wendy's.)

For Seeger, music is not about financial gain but reaching individuals. "The most important thing I've done in my life," he said, "is to show that you don't have to have hit songs on the radio. I showed a raft of young composers you don't have to chase after the music business to try and make a living. You should sing for whoever you want—a coffeehouse here, a little organization there who needs a singer for an evening, from school to school." He credits this to his helping opening up the college performing circuit in the late 1950s. "I just got on the stage and sang informally, and said: hey, help me out with the chorus," he said. "It opened up a new field for performers—Buffy Sainte-Marie, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Graham Nash, David Crosby, and a whole lot of others. I could have kicked the bucket in 1960, and my main job was done." From another room, Seeger's wife, Toshi Seeger, shouted: "I thought marriage was your main job." "My main musical job," Seeger corrected.

He's more popular now, he feels, than he's often been in his long career, especially during his tempestuous 1950s and '60s period when his records were burned, he had difficulty appearing on television, and was an all-but-pariah from mainstream society. Now, the stigma has been lifted—Musselman jokes that "he went from the blacklist to the A-list in a number of years"—and younger generations are again embracing him as an American treasure. The singer appreciates the attention, but it comes with pitfalls. "The phone rings all day long," he sighed. "The mail comes in by the bushel." Once known for responding to fan mail personally, Seeger now receives far too much; still he feels obligated to respond to each person with one of several form letters he's written. "Until that nice movie [PBS Documentary] The Power of Song came out, I lived a halfway normal life. But now I've blown my cover," one starts, apologizing for the stock response. He's reserved an acerbic letter for autograph-seekers. It begins: "I wish I could persuade you that collecting autographs is one of the most foolish ways we can spend our precious time." When discussing the deluge of fan mail, or phone calls from reporters, it's the only time Seeger really sounds like a 91-year-old man.

Change the topic to music again, though, and he's reanimated. Seeger's working on recording a new song, called "God's Counting on You," a long, stanzaic ballad with what he insists is the key ingredient of successful protest music—a catchy chorus that's fun to sing. He rattled off a few verses a cappella, one of which is especially timely: "Yes, when drill, baby, drill / Turns to spill, baby, spill / God's counting on me / God's counting on you."